Article

Executive Summary

Canadians enjoy a thriving, vibrant and highly competitive financial sector. It is characterized by hundreds of financial services companies of different types and business models, of which banks are an important subset, which serve Canadian consumers. Banks compete against one another, established financial sector companies, emerging firms with new business models, as well as large multinational technology companies with strong brand presence. As a result, competitive intensity within the financial sector has never been higher due to investments in technology with companies entering, expanding and/or exiting the sector at a rapid pace.

The level of concentration of banking assets in Canada is not unusual amongst industrialized countries and does not suggest a problem that requires a solution or regulatory intervention. The key markers of a healthy, competitive banking and broader financial sector are all present. There is entry, expansion, exit; significant investments in technology; ample consumer choice and satisfaction; and robust competition between participants, underpinned by trust and confidence in the banking sector.

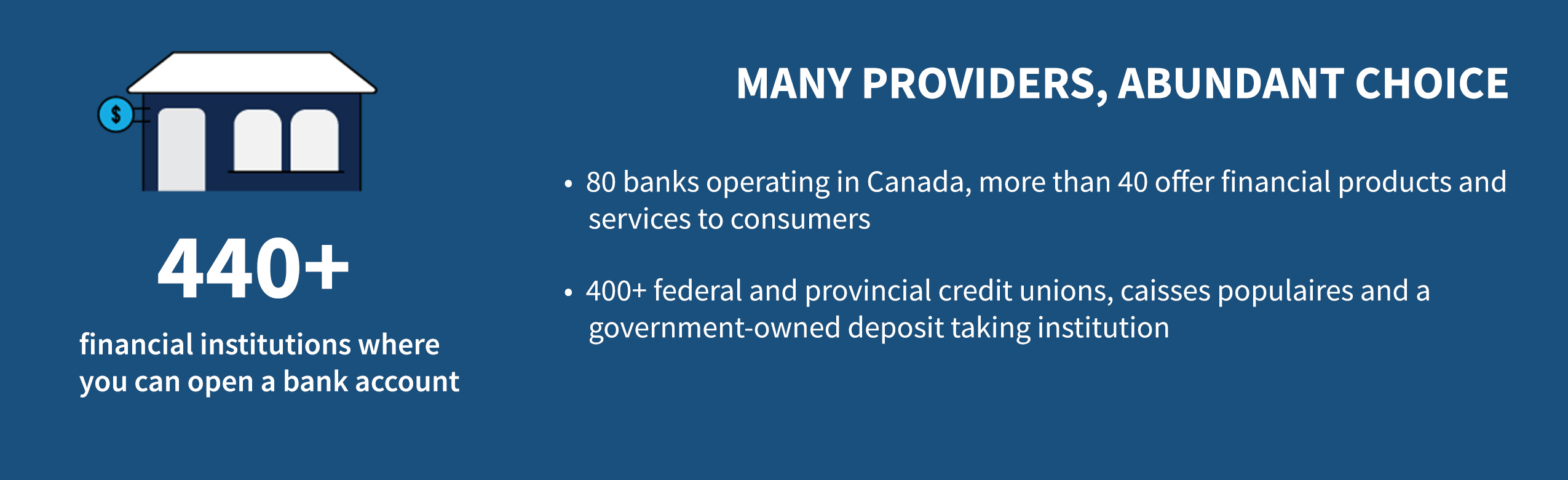

As a result of competition in the financial sector, banks are investing in technology to adjust to consumers’ evolving preferences, behaviours and needs to improve the customer experience. Consumers are the ultimate beneficiaries of this investment through increased accessibility, choice, affordability and contestability. For instance, in the market for bank accounts, nearly all working‑age Canadians have an account at a financial institution1, roughly 57 per cent of Canadians either did not pay for a bank account or had their monthly fee waived or refunded in the last month2 and there are nearly 450 deposit‑taking financial institutions where a bank account can be opened.3 Robust competition is also present in payments, mortgage, small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) lending as well as other financial services markets.

Banks are strong proponents of an open, competitive and stable financial sector to benefit consumers. As banks play an important role in the financial system and broader economy, the sector has a significant stake in ensuring the financial system continues to be competitive and to provide affordable and accessible services within a system that also maintains safety, security and stability for consumers. A growing number of competitors, including fintech firms and bigtech companies, are entering the financial sector, who are engaged in equivalent activities as banks. However, they are not subject to the robust bank regulatory framework that helps keep Canada’s financial sector and Canadians safe.

Considering these factors, the Canadian Bankers Association (CBA) provides a number of recommendations4 to facilitate better adaption to changing consumer expectations, preferences and behaviours; more effectively incorporate technology; improve consumer protection; apply consistent regulatory oversight of companies in the financial sector; and increase competition within and the competitiveness of the sector. These are:

- Bring into force the "Fintech Amendments";

- Address regulatory compliance burden on banks;

- Implement consistent regulation to support consumer trust in emerging competitors – for example, market conduct regulation of Payment Services Providers (PSPs);

- Respect the principle of proportionality of regulation for small- and medium-sized banks;

- Streamline credit union expansion;

- Make policy and regulatory frameworks digital‑first including defaulting to electronic communications and digital exchange of income and registered plan contribution limit data with taxpayer consent;

- Repeal section 49 of the Competition Act; and,

- Remove financial sector‑specific taxes.

In addition, the CBA believes that a robust merger review process for bank mergers that combines prudential and public interest considerations with an analysis of the impacts of a merger on competition is already in place and overseen by the Minister of Finance with input from the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) and the Commissioner of Competition. Banks do not believe there is a need for significant changes to the current process. In particular, the CBA does not support abandoning the current fact- and evidence-based analysis of the economic, consumer and public interest impacts of a merger.

Introduction

The CBA welcomes the opportunity to respond to the Consultation on Strengthening Competition in the Financial Sector issued by the Department of Finance (Finance). The CBA is the voice of more than 60 domestic and foreign banks that help drive Canada’s economic growth and prosperity. We advocate for public policies that contribute to a sound, thriving banking system to ensure Canadians can succeed in their financial goals.

Canada’s banks have a longstanding and continuing record of supporting our country’s economy and investing in our communities. In 2022, they contributed approximately $70 billion (or 3.6 per cent) to Canada’s GDP, paid close to $18 billion in taxes to all levels of government, and provided $26 billion in dividend income to Canadian seniors, families, pension plans, charities, and endowments. The industry has invested approximately $115 billion in technology across Canada over the last decade and operates a network of over 5,600 branches and close to 19,000 automated banking machines (ABMs) across Canada providing accessible, affordable, and competitive banking services. The banking industry employs more than 280,000 people throughout the country, a workforce that is inclusive, equitable, and talent driven.

Banks also play an important role in the household and business financing ecosystem. According to CBA statistics, at the end of 2022, banks in Canada have lent, in total, more than $1.5 trillion in residential mortgages and authorized $1.7 trillion in business credit, of which $278 billion was authorized to SMEs.

The sector is well‑managed and well‑regulated, and banks operating in Canada are internationally recognized as among the world’s most safe, demonstrating stability for the long term and during challenging times. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, banks offered significant relief to Canadians and also worked in lockstep with the government to help deliver Canada Emergency Business Account (CEBA) loans to nearly 900,000 small businesses, and quickly and securely delivered emergency benefit payments to Canadians who needed them. Banks were able to achieve this broad outreach to Canadians, in large part, through trusted digital channels.

State of Competition in the Financial Sector

Technology has facilitated the entry of, and allowed for greater scale for, bank and non-bank financial sector companies, thus increasing competition and competitive intensity in the sector. Because of this increased competition, financial sector companies are incorporating technology into their business models to improve the customer experience. As a result, competitive intensity within the financial sector has increased, with contestability for the financial consumer never being higher.

Banks compete against each other, other established players such as provincial credit unions and caisses populaires, government‑owned deposit‑taking and finance institutions, life and health insurance companies, general insurance companies, trust companies, mutual funds, securities dealers, pension managers, investment advisers and specialized finance companies – all of whom are leveraging digital financial technologies and innovative business models to varying degrees.

In addition, the banking sector as well as other established financial sector companies are part of an ever‑expanding ecosystem of new entrants emerging in the competitive landscape. The combination of maturing digital technology, steady growth and adoption of e‑commerce, and strong investment climate for innovative business models has fostered the growth of new types of financial sector fintech firms such as payment services providers, buy‑now‑pay‑later companies, digital currency exchanges, robo‑advisors, and other business models that were never contemplated when most of Canada’s financial sector legislative architecture was designed. According to Tracxn, there are more than 3,800 of these firms in Canada as of June 2023.5

Furthermore, large multinational technology companies with strong brand presence are increasingly expanding their presence into the financial services marketplace. These global technology giants are becoming central players in the Canadian financial sector, yet they are not subject to the robust bank regulatory framework that helps keep the sector, and Canadians, secure. These companies engage in equivalent activities as banks, carrying equivalent risk, and should be subject to the same regulations based on the principle of ‘same activity, same risk, same regulation’. Further, these new, large entrants are not hindered by outdated rules around information technology and electronic communications that exist under the Bank Act.

Competition within the banking sector

The Canadian banking sector provides affordable, accessible, and innovative products and services within a highly competitive system that provides reliability, security and stability for depositors and investors. A particular level of concentration in the banking sector does not suggest a problem that requires a solution or regulatory intervention. The key markers of a healthy and competitive banking sector are all present - exit, expansion; significant investments in innovation; ample consumer choice; and robust competition between participants underpinned by trust and confidence.

The sector itself is composed of 80 domestic banks, foreign bank subsidiaries, foreign bank branches and federal credit unions. In summary, the Canadian banking system includes:

Type of institution

Services provided

Domestic Systemically Important Banks (DSIBs)

- Diversified personal and commercial banking

- Wealth management

- Corporate and institutional banking

- Capital markets

- Equipment financing

- Other services

- Diversified personal and commercial banking

- Wealth management

- Capital markets

- Equipment financing

- Other services

- Diversified personal and commercial banking

- Wealth management

- Capital markets

- Equipment financing

- Other services

- Diversified personal and commercial banking

- Wealth management services

- Largely credit card services on an online-only platform

Foreign bank subsidiaries

- A mix of personal and commercial banking

- Wealth management

- Corporate and institutional banking

- Capital markets

- Typically provide corporate and institutional banking services as they are limited in their ability to collect retail deposits6

In recent years, the Canadian banking sector has seen the number of banks grow. This has resulted in banks owned by a telecommunications company, grocery and department stores, and a life and health insurer, as well as federally-chartered credit unions. In March 2003, there were 70 banks; in 2023, that number grew to 80 banks. The number of domestic banks that typically specialize in personal and commercial banking have more than doubled.7 On average, one new domestic bank has been incorporated each year since the turn of the millennium, with at least two more financial sector companies seeking approval for a domestic banking license from OSFI, demonstrating lower barriers to entry and exit over the years.8

Concentration in the banking sector

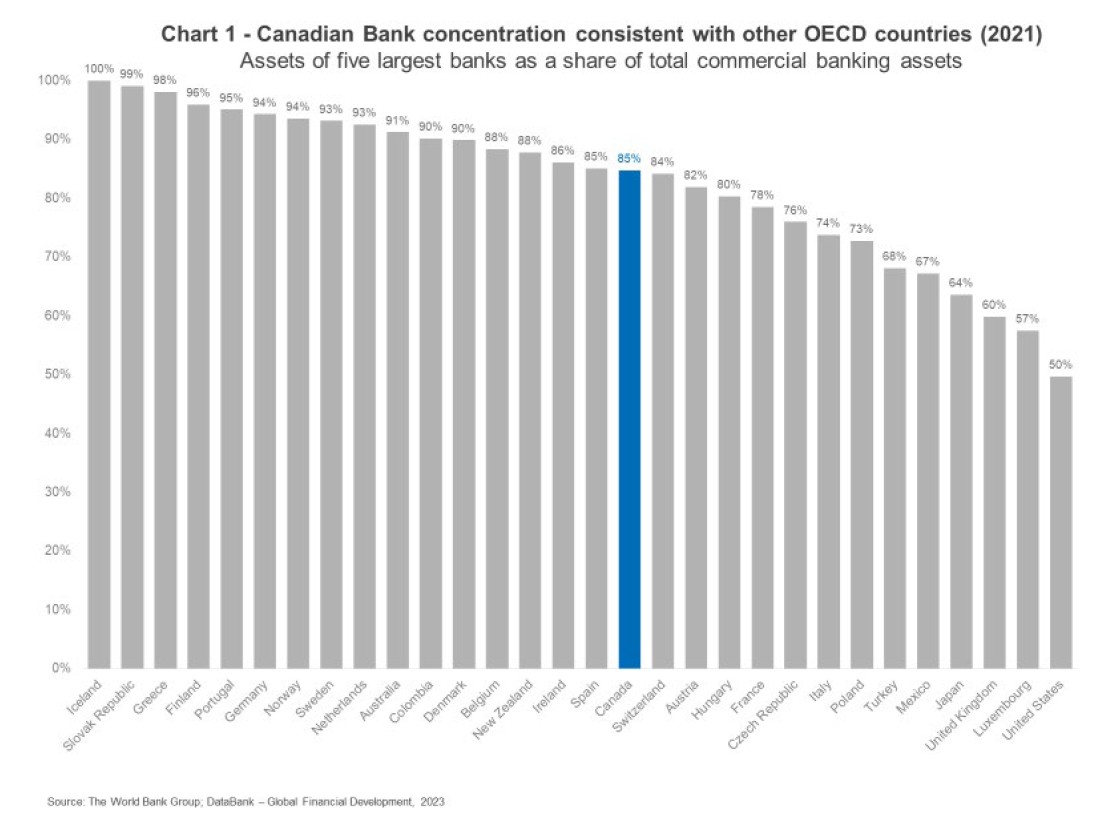

According to the World Bank9, the five largest banks account for 85 per cent of commercial bank assets in Canada in 2021. This level of concentration of banking assets is not unusual among industrialized countries. This ranks the Canadian banking system in the middle of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) economies in terms of concentration with ten countries having rates of concentration of over 90 per cent, including Germany, Australia and New Zealand (Chart 1).

Despite this, the OECD has underscored that market concentration should not be confused with market power or competitive intensity, which is what matters for consumers. While concentration can be an indicator of market power, it is far from determinative and in fact it says very little about whether or not competitive intensity is changing10 nor does it account for the financial services that are provided by non-banks offering substitutable products and services within a jurisdiction which is particularly true for Canada.

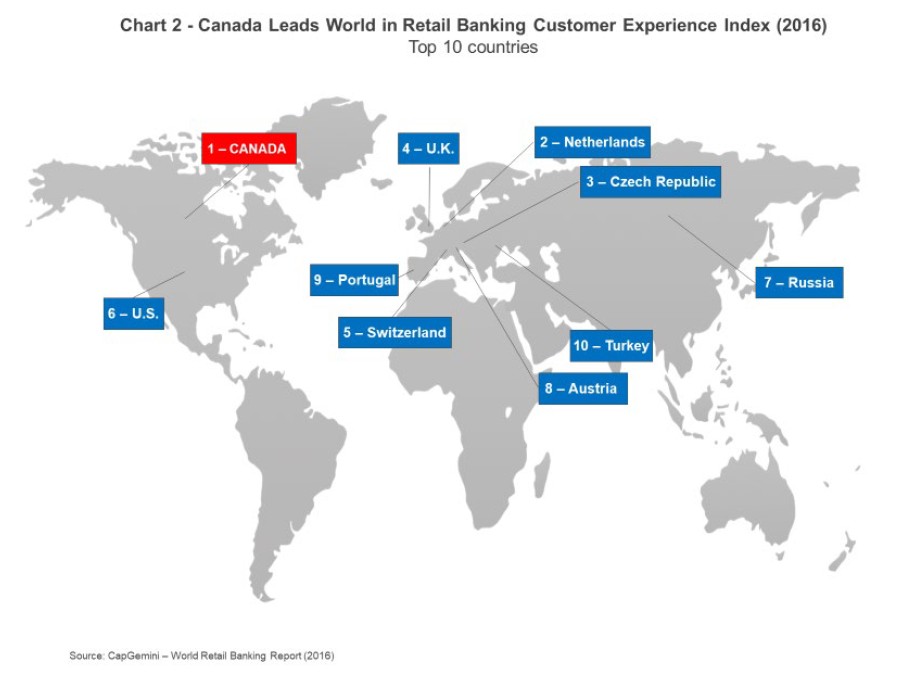

Indeed, the evidence shows that the level of concentration of banking assets in Canada does not determine the quality of banking services that customers receive. Canadian retail banking customers demonstrated the highest level of positive customer experience and customer satisfaction among 14,000 retail banking customers across 35 countries in North and Latin American, Europe and Asia Pacific for CapGemini’s Customer Experience Index (CEI) over six years. The Index measured customers’ banking experiences across 80 different touch points encompassing products, channels and life cycle stages.11 An early CapGemini Report called out the solid performance of Canadian banks throughout the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), as well as increased investment in customer‑focused technology.12 In 2016, the last year of the CEI Survey, Canadian banks ranked #1 in the CEI, ahead of the U.K., U.S., Australia and the global average, illustrating the benefits to consumers of competition within the banking sector and with other parts of the financial sector (Chart 2).

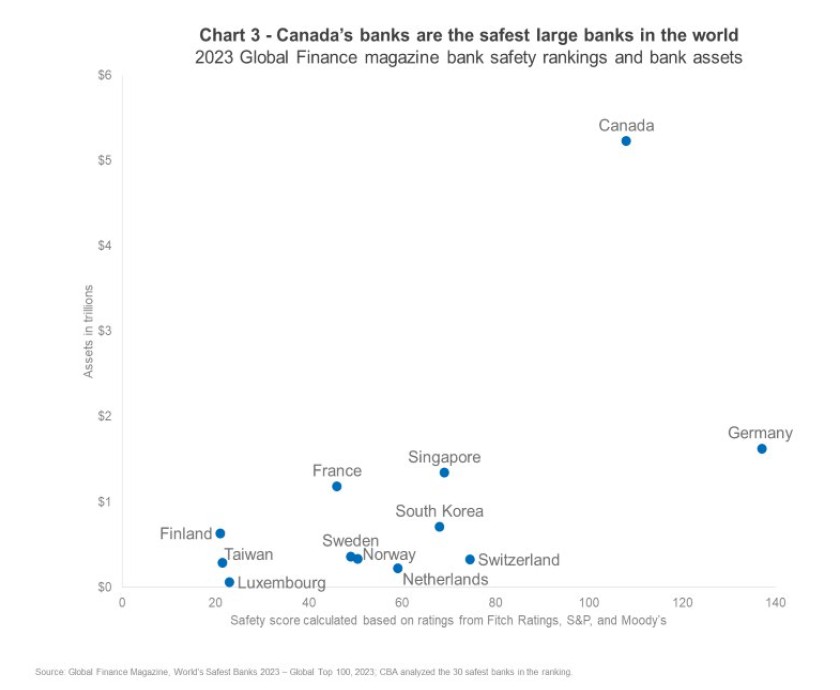

Confidence and trust are the foundation of any banking system. While events such as the GFC and the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) last year test the resiliency of the global financial system, Canadians continue to have a high degree of confidence and trust in their banks when compared to other banks internationally and other companies domestically. To a large degree, this high degree of confidence and trust is the result of the Canadian banking sector’s long track record of providing a balanced supply of banking services relative to the economy in comparison to the experience of other countries such as the U.S. who have experienced vacillations between periods of imbalances (where there is either an oversupply or undersupply of banking services relative to the economy) and balance.13 Canadians acknowledge this track record of balance. For instance, coming out of the GFC, Canadians ranked their banks as the most sound in the world for eight straight years and in the top three for eleven straight years.14 This high degree of trust and confidence is also illustrated in the strength and value of bank brands, with five Canadian banks among the top 10 most valuable and strongest brands in Canada in 2023.15 Furthermore, the same five banks are the safest in North America, and are the safest large banks in the world (Chart 3).16

Consumers trust and confidence in the banking sector are further reflected in recent CBA surveys where 86 per cent of Canadians state that they trust their bank to offer secure digital banking services, and 87 per cent trust their bank to protect their personal information.17

Impact of technology on competition in the financial sector

Banks in Canada are leaders in the development and adoption of new technologies to meet evolving consumer preferences and behaviours, including more personalized and accessible banking experiences and applying technology to simple and routine self-serve financial transactions in order to focus employees’ time on providing high‑value advice and other helpful solutions for consumers. Consumer preferences and behaviours are influenced by access to real- and any‑time information which has grown exponentially in recent times, use of a growing and diverse number of internet‑connected devices (smartphones, watches, tablets, and personal computers) to connect digitally, and increased technology proficiency. Banks face tremendous competition from established financial sector companies, emerging fintech firms with new business models, as well as large multinational technology companies with strong brand presence.

Examples of how banks incorporate technology to serve customers include:

- Internet banking enables customer‑directed 24/7 banking access with consumers conducting over 400 million transactions in 2021.18

- Smartphone applications have enabled consumers to conduct close to 1 billion transactions on their mobile phones in 2021.19

- Security features on payment solutions such as chip and PIN, data encryption, artificial intelligence and biometrics significantly reduce the incidence of fraud for point‑of‑sale transactions.

- Payments have been made more convenient through the introduction of contactless payments, in respect of which Canada is a leader globally, as well as through mobile wallets and mobile cheque deposits.

- Interac e‑Transfer®, a real‑time P2P solution, is offered both online and via mobile.

- Security features such as ID verification technology to authenticate a client remotely.

- Applications have been developed that allow for expense tracking, budgeting, investment and fraud identification tools that are designed to enhance consumer understanding of, and control over, their finances.

- Use of artificial intelligence (AI) to provide banking customers with personalized, automated, and actionable insights as well as front‑line employees to serve those customers. Four Canadian banks are ranked amongst the top twenty global banks for AI readiness.20

- Experimenting with and leveraging technology such as virtual and augmented reality as well as browser plug‑ins to enable consumers to personalize their digital banking experiences with their individual accessibility preference.

As a result, Canadians generally feel that their banking experience has improved. Indeed, in 2022:

- 90 per cent of consumers believe that new technologies have made banking a lot more convenient;

- 86 per cent of Canadians agree that their bank has improved service through technology; and

- 78 per cent of Canadians are using digital channels to conduct most of their banking transactions (up from 76 per cent in 2018 and 68 per cent in 2016).21

Competition within specific products and services

As a result of competition amongst banks and with non-banks, Canadian consumers are increasingly benefiting from a full range of accessible and affordable financial products and services across product lines such as bank accounts, payments, mortgages and SME loans.

Bank accounts

A bank account is the most basic financial product that a customer needs to access the financial system, as it is used to hold funds and record transactions. Canadian banks offer a variety of bank accounts for customers – including basic chequing and savings accounts; full‑service accounts with many types of transactions; low‑fee or no‑fee accounts; youth, student and seniors’ accounts; foreign exchange accounts, etc. More than 40 banks offer 100 different bank account packages to customers. In addition to banks, over 400 non‑banks (provincially‑regulated credit unions and caisses populaires and ATB Financial) offer bank accounts.22 Bank accounts are available to individuals even if they don’t have money to put into the account right away, don’t have a job or a credit history or have been bankrupt. And this can be done in person, digitally (online and mobile), using an ABM or by telephone.

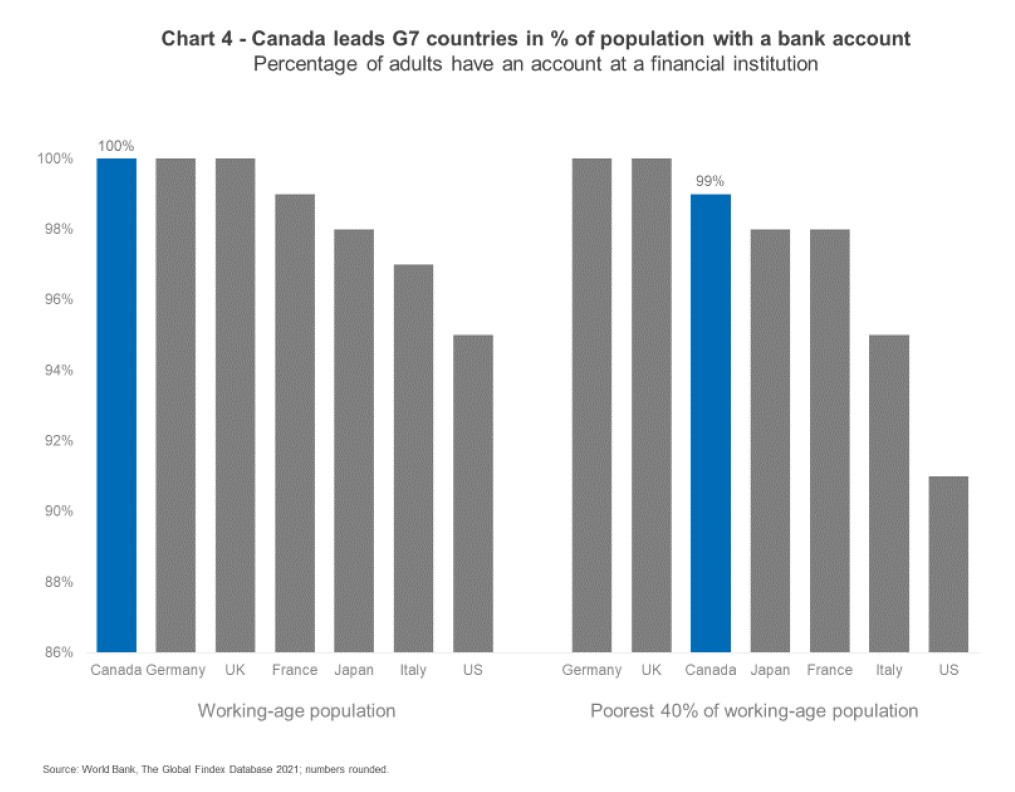

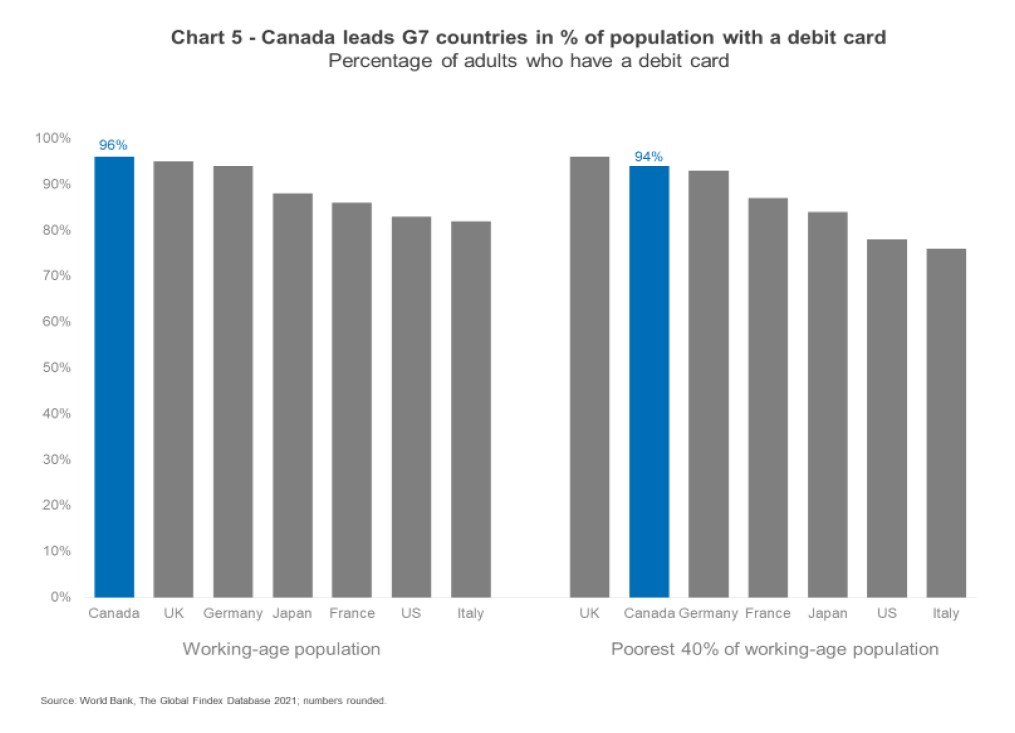

As a result of this competition, Canada’s financial system is the most inclusive financial system in the G7 group of countries and a global leader in high‑income economies. According to the World Bank, nearly all working‑age Canadians have an account with a financial institution and 96 per cent of working‑age Canadians have a debit card, including the poorest 40 percent of the working-age population (Charts 4 & 5).23

Competition has led to affordable bank accounts for consumers. According to the Bank of Canada, in 2022, 37 per cent of respondents with a bank account reported not having an account fee, up from 27 per cent in 2017. Furthermore, 31 per cent of Canadians with a monthly bank account fee had it waived or refunded in the last month in 2022.24 Technology has made it easy for consumers to compare banks accounts either directly at a bank’s website or branch, private sector financial comparator websites or the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada’s (FCAC) Account Comparison Tool.

Payments

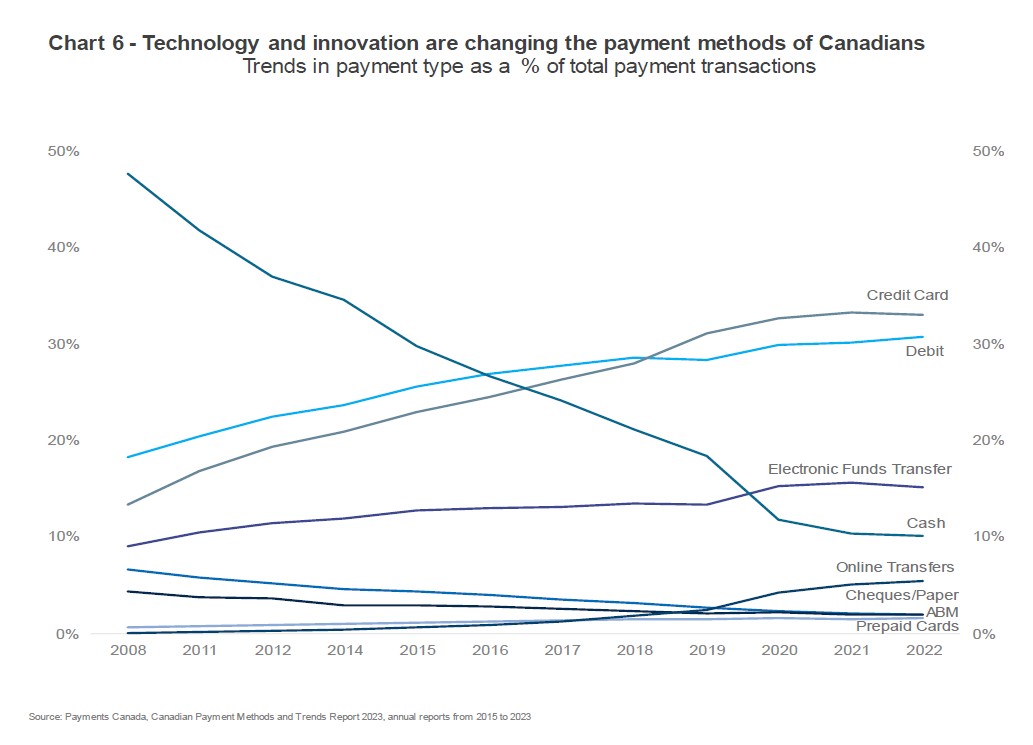

Canadians have a wide variety of options to make payments – cash, debit cards, credit cards, mobile payments, online banking, electronic funds transfer, cheques and prepaid cards. Technology has evolved both consumer preferences, behaviours and needs, and financial institutions’ ability to address and adapt to them. Canadians’ demands for digital means of payments have increased over the last fifteen years and it was accelerated by the COVID‑19 pandemic. For instance, in 2008, 55 per cent of all transactions were conducted in either cash or cheque. On the other hand, online transfers, credit cards, electronic funds transfers and debit cards were the source of 44 per cent of all transactions. By 2022, only 12 per cent of all transactions were conducted in either cash or cheque while 84 per cent were conducted by online transfer, credit card, electronic funds transfer or debit card (Chart 6).

Banks compete against each other, other established players such as provincial credit unions and caisses populaires, and government owned deposit taking institutions to provide a range of payment services, including credit and debit cards, online banking, and mobile apps that are highly accessible and affordable.

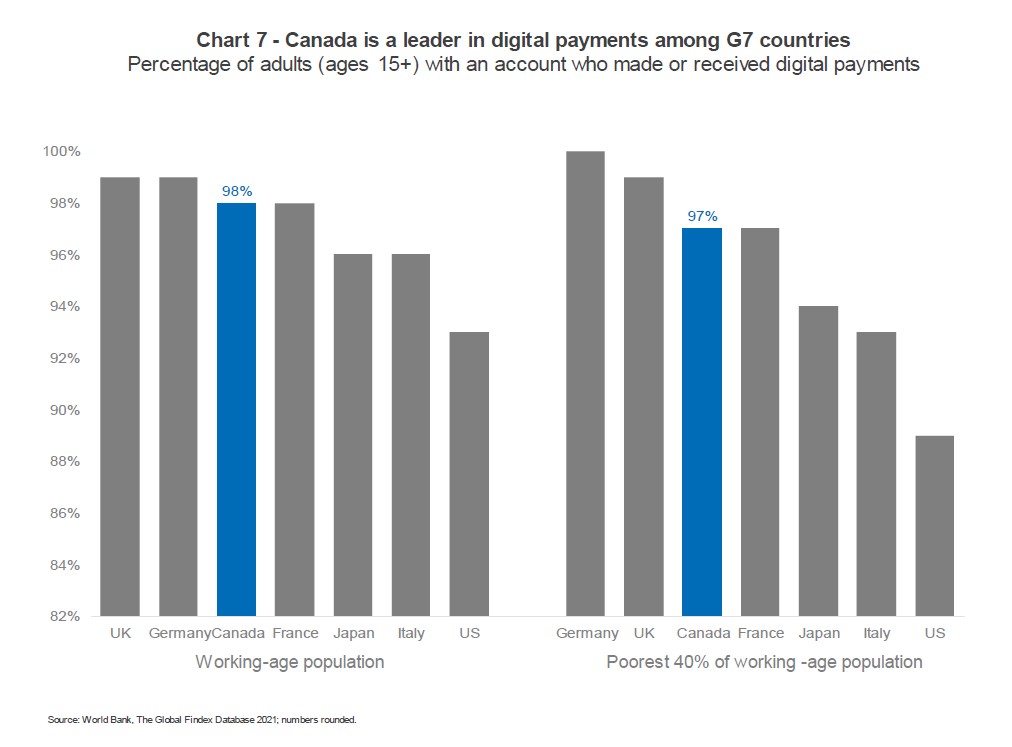

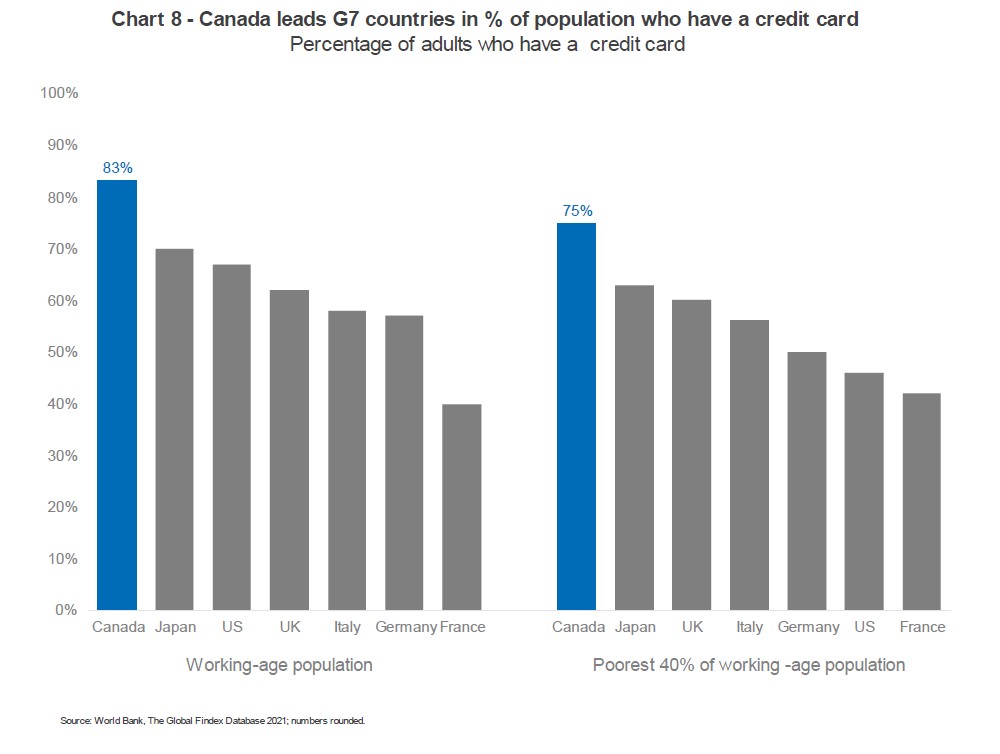

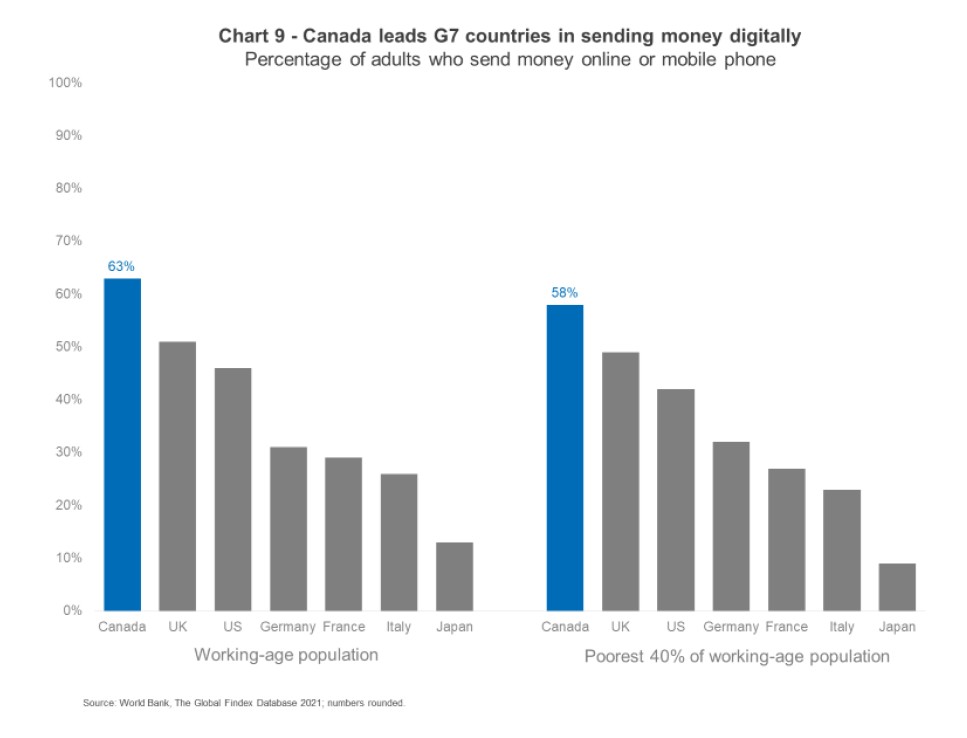

As a result of this competition, Canada’s financial system is the most inclusive financial system in the G7 group of countries and a global leader in high-income economies. According to the World Bank:

- 98 per cent of working‑age Canadians have made or received a digital payment.

- 83 per cent of working‑age Canadians have a credit card.

- 63 per cent of working‑age Canadians have used a mobile phone or internet to send money – the highest in the G7.

Moreover, these penetration rates do not vary significantly with income. Even if we remove the top 60 per cent of working‑age earners and concentrate on the remaining 40 per cent, the result remains that the overwhelming majority have made or received a digital payment (97 per cent), have a credit card (75 per cent) and a large majority have used a mobile phone or internet to send money (58 per cent) – the highest in the G7 (Charts 7, 8 & 9).

While the payments market is predominantly defined by banks and other deposit‑taking financial institutions, other non‑deposit‑taking institutions have leveraged technology to meet Canadians’ growing demand for digital payments. The Bank of Canada estimates that there are more than 2,500 PSPs, such as digital wallet apps, payment account apps and store‑branded prepaid card apps, provide the ability to hold funds and record transactions, as well as other features and services that can influence what consumers expect from banks and other deposit taking institutions. An increasing number of Canadians are using these apps with 18 per cent of Canadians using digital wallet apps, while 9 per cent and 8 per cent of Canadians used payment account apps and stored value cards, respectively.25

Mortgages

For many borrowers, a mortgage is the most important financial decision that they will make in their lifetimes. Canadian banks offer a variety of mortgages for customers – including fixed, variable, or hybrid rate mortgages with different terms and amortizations; those with lines of credit attached; fixed and variable payments; differing payment schedules and options; reverse mortgages; and more. This is the result of the high degree of competition within the mortgage market.

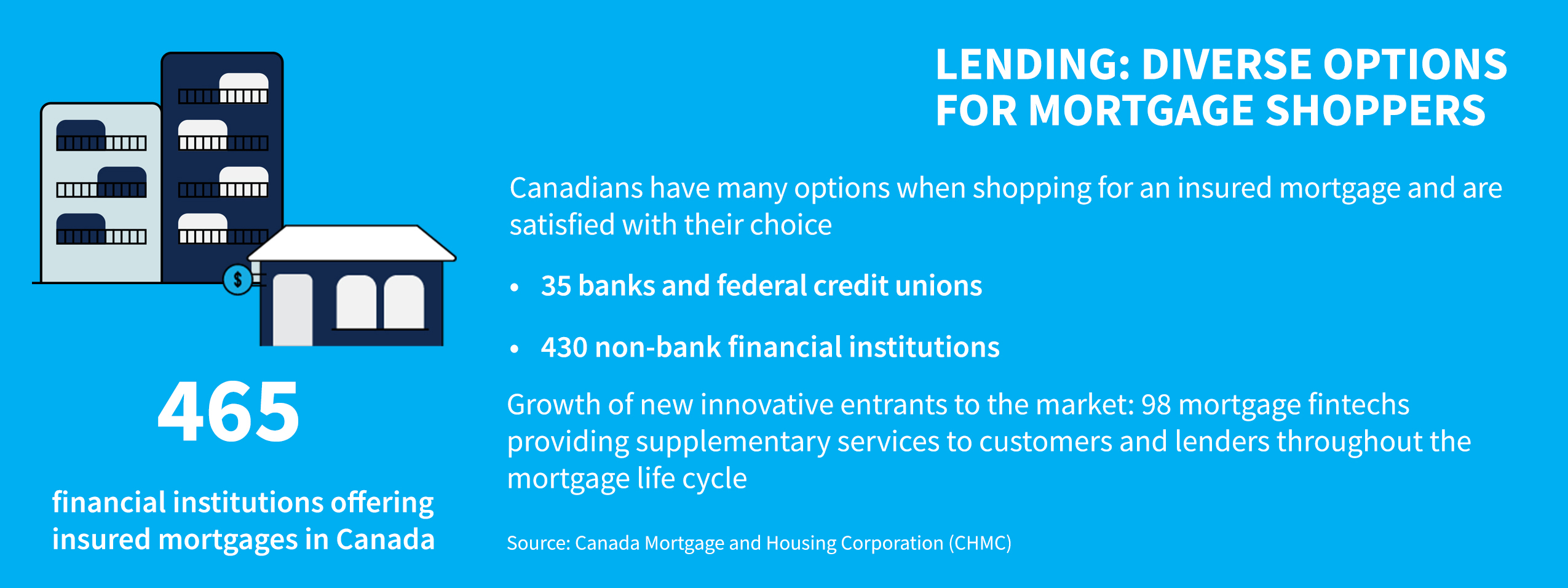

According to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s (CMHC) list of National Housing Act Approved Lenders, there are 35 banks and federal credit unions providing insured mortgages in Canada, in addition to nearly 430 non‑bank financial institutions such as provincial credit unions, caisses populaires, mortgage finance companies, trust companies, insurance companies, and a government‑owned deposit‑taking institution.26 Most of these lenders participate in the uninsured mortgage market and compete against other actors such as mortgage investment corporations, private lenders and other lenders.

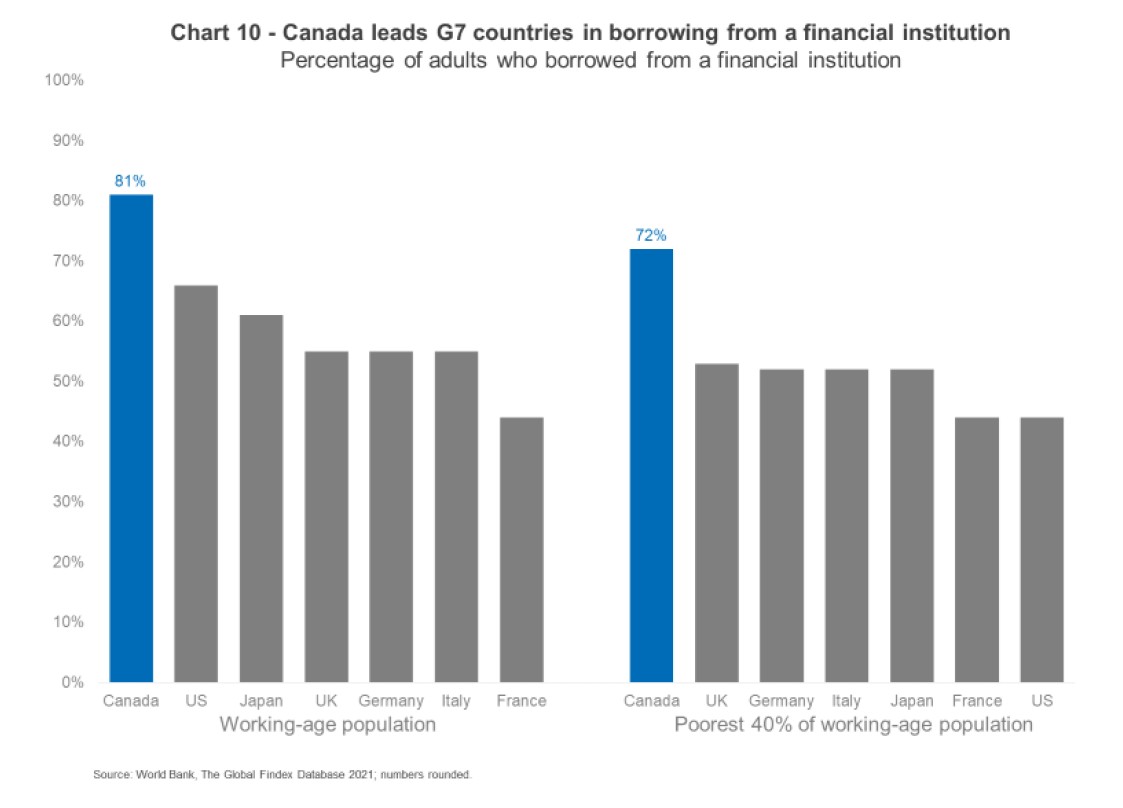

These lenders use a variety of channels to reach consumers such as online and mobile channels, in‑branch agents, mobile mortgage specialists, mortgage brokers and online price comparison websites. Through these channels, consumers can access a wide range of online information tools to educate themselves ahead of the mortgage borrowing process. Indeed, according to the World Bank, 81 per cent of working‑age Canadians (and 72 per cent of the poorest 40 per cent of the working‑age population) have borrowed from a formal financial institution (Chart 10).27

Generally, consumers are highly satisfied with the mortgage process. For instance, in a CMHC survey of mortgage borrowers, the proportion of consumers that stated that they were confident that they received the best mortgage deal for their needs increased to 86 per cent in 2022 from 77 per cent in 2019, falling to 70 per cent in 2023 because of the higher interest rate environment. This is consistent with a 2022 Mortgage Professionals of Canada survey where 84 per cent of respondents answered positively about being happy with the competitive mortgage rate they received, as well as their level of satisfaction with their mortgage professional (lender or broker).28

Further, there has been a growing number of new players with new business models entering the mortgage market. According to a joint Deloitte/CMHC report published in October 2020, there were 98 mortgage fintechs active in Canada in 2019 with different operations across the mortgage cycle, with approximately 33 of them specializing in origination or underwriting.29

The same report noted that banks in Canada have played an active role in the development and adoption of mortgage technology. In recent years, banks have supported the development of innovative technologies – either through in‑house initiatives or collaborative partnerships and that encouraging collaboration between banks and fintechs can be a positive step towards supporting innovation in the mortgage industry.30

SME loans

For many SMEs,31 access to financing is an important component to their growth and sustainability. Banks in Canada offer a variety of SME loans for their customers including short‑term and operating loans (including overdraft facilities), asset‑based lending, mid‑term and long‑term business loans, commercial mortgages, equipment financing and leasing, credit cards as well as business loan insurance, with a variety of features including fixed or variable interest rates with different terms, amortizations and prepayment options.

According to Statistics Canada’s Survey of Suppliers of Business Financing, there are at least 120 financial services companies providing business financing, including to SMEs.32 These financial services companies include banks, credit unions, caisses populaires, finance and leasing companies, financial Crown Corporations, insurance companies, and portfolio managers.33 This competition is one of the reasons why SMEs are well‑served.

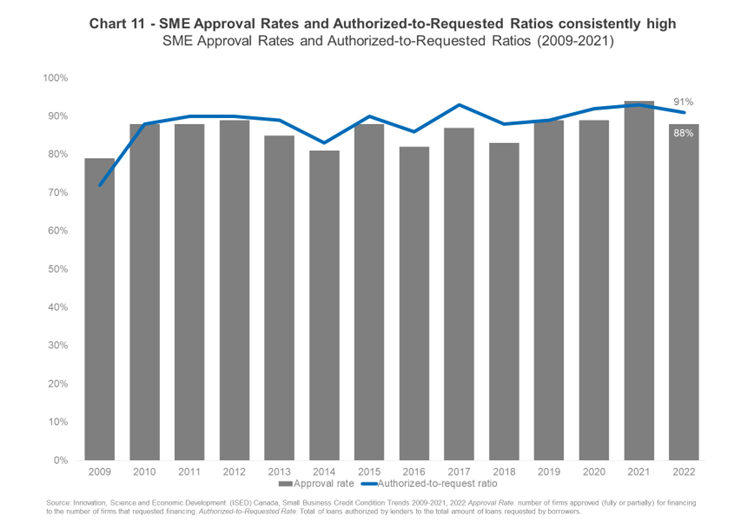

Indeed, according to Statistics Canada, 88 per cent of SME’s debt financing requests were approved in 2022 with the approval rate consistently being above 80 per cent since the GFC. And of those SMEs that were approved for debt financing, the ratio of total funds authorized‑to‑requested was 93 per cent in 2021, with the funds authorized‑to‑requested consistently about 80 per cent since the GFC. The average amount authorized has increased for businesses of all sizes, regions and industrial sectors since the GFC (Chart 11).

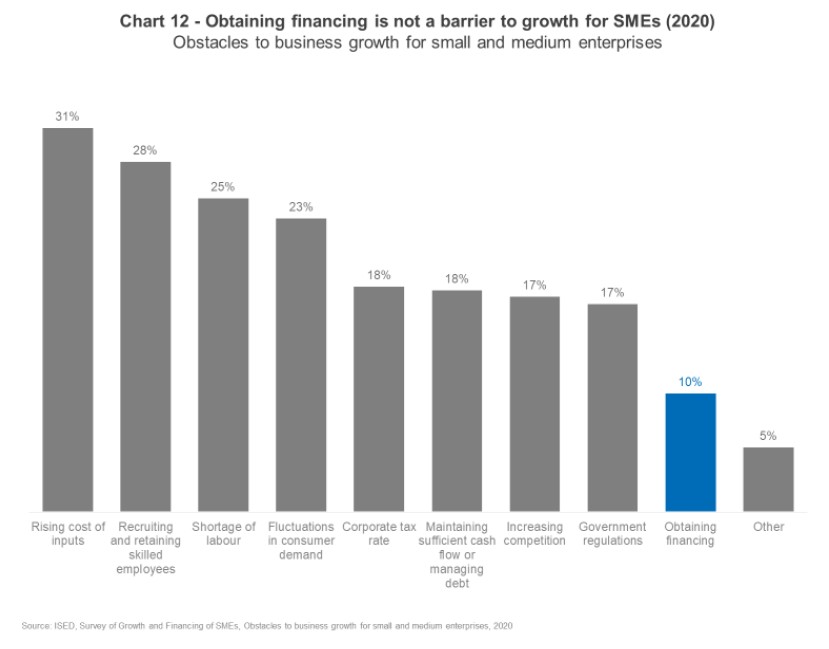

Lastly, SMEs consistently identify non-financing (rather than financing) factors as being the primary constraints to growth and production such as rising costs of inputs, skilled and unskilled labour shortages, taxation and government regulation (Chart 12).34

Recommendations

Banks are strong proponents of an open, competitive and stable financial sector to benefit consumers. As banks play an important role in the financial system and broader economy, the sector has a significant stake in ensuring the financial system continues to be competitive and to provide affordable and accessible services within a system that also maintains safety, security and stability for consumers. While the banking sector has performed well when measured by accessibility and affordability and incorporating technology to provide an excellent customer experience, there are ways that consumers can benefit more from the banking and, broader, financial sector experience.

At the same time, there are a growing number of competitors in the financial sector that are not subject to the robust bank regulatory framework that helps keep Canada’s financial sector and Canadians safe. These companies engage in equivalent activities as banks, carrying equivalent risk, without being subject to the same regulatory framework.

The recommendations the CBA makes below will:

- Allow the financial sector to better adapt to changing consumer expectations, preferences and behaviours;

- More effectively incorporate technology in the regulatory landscape;

- Improve consumer protection;

- Apply consistent and proportionate regulatory oversight of companies in the financial sector; and,

- Increase competition within the financial sector and the competitiveness of the sector as a whole.

Bring into force the "Fintech Amendments"

The Fintech Amendments were introduced by the Government and passed in 2018 as priority amendments to provide greater flexibility for FRFIs to undertake and leverage broader fintech activities that enable the delivery of financial services in new and innovative ways. It is absolutely essential that the Fintech Amendments be brought into force to enable federally‑regulated financial institutions (FRFIs), such as banks, to continue to compete effectively and provide consumers with the technology‑enabled products and services they increasingly demand. The accompanying regulations that are required to enable FRFIs to rely on the Fintech Amendments, however, still have not been promulgated. Given the dynamic nature of the financial services market, these amendments to the legislative framework were appropriately recognized as critical to ensure it maintains its utility and is responsive to the evolving preferences and expectations of Canadians while continuing to foster stability for the benefit of the Canadian economy.

Since 2018, the continuing acceleration of technological advances in our daily lives (e.g., generative AI) and the broad‑based shift to digital channels accelerated by the pandemic have significantly changed customer expectations and only serve to underscore the urgent need for FRFIs to use the tools that the Fintech Amendments were intended to provide. Many underregulated or unregulated serviced providers, including multinational technology giants, have entered the financial sector to provide technology-enabled services, and banks are eager to deploy additional powers under the Fintech Amendments to more effectively compete, innovate, and ultimately provide customers with the products and services that they prefer.

Beyond the ability to compete, the technological evolution of the financial services ecosystem is creating an environment where partnerships and collaboration among banks and non-bank providers can also enhance the capacity for responsible innovation to occur. As an example, non‑bank providers can develop areas of specialized expertise for particular products or services, while banks have the platforms, client base and investment capacity to leverage these capacities at scale for the benefit of a wide range of consumers and the system as a whole. The Fintech Amendments would ease constraints on the ability of banks to enter into these types of collaborative arrangements, which we believe could be critical to ensuring that Canada remains at the forefront in providing leading‑edge technological capabilities for Canadians in a safe, secure and stable environment.

Related to the above point, we would note more generally that it is increasingly important to view the financial sector as a cohesive whole, rather than as segments that should be played off against each other. Large-, mid- and small banks as well as non‑bank financial services companies can each have a role to play in the ecosystem and their respective strengths should be leveraged to the highest extent possible to promote a sector that is greater than the sum of its component parts. In light of this perspective, we recommend balanced and holistic measures designed to improve the strength and vitality of the system as a whole so that each segment can contribute in their own unique ways.

Implement consistent regulation for all financial sector companies to support trust

Consistent regulation of emerging fintech and bigtech competitors would increase consumer trust and confidence in these companies and support their growth. Most significantly, there needs to be consistent market conduct (consumer protection) rules for fintech firms and bigtech companies as well as banks, which will require the federal government and provincial governments to work together toward harmonized outcomes. We believe the federal government should play a leadership role in this regard to ensure that Canadians continue to benefit from secure and reliable financial services and that the unregulated players do not introduce risks into our existing stable financial system. Ultimately, such a regulatory framework would abide by the principle "same activity, same risk, same regulation".

Market conduct regulation, which includes consumer protection measures, is critical for promoting trust and confidence in Canada’s financial system and for ensuring that users are treated fairly and consistently.

Such market conduct regulation should include measures comparable to those in place for regulated financial institutions, such as:

- A disclosure regime that requires financial service companies to accurately inform users about their services including:

- service charges, including transaction fees, foreign exchange rates, interest payable to end users on safeguarded funds, etc.;

- how and when a customer may access funds in the hands of a financial service companies;

- A minimum standard for how quickly a financial service companies must provide end users with appropriate and timely access to their funds. For example, a requirement to return funds within a prescribed number of business days following an end user request;

- Requirements to provide accurate records and/or statements of funds balances and transactions to end users, and a process to enable end users to obtain corrections of inaccurate records;

- An internal dispute resolution process, including a clear pathway for end users to raise and escalate complaints as well as timelines for responses and resolution; and

- A process on how a financial service company must notify a customer of changes to its fees or to any other user term.

The absence of market conduct standards creates significant risks to consumers and other end users dealing with a newer competitor that might not accurately disclose information to them; or may not have robust processes in place to correct errors, manage complaints, or allocate liability for unauthorized transactions.

Market conduct regulation of Payment Services Providers (PSPs)

An example of where there needs to be consistent regulation to support trust in emerging competitors is with market conduct regulation of PSPs. The Retail Payment Activities Act (RPAA) was passed in June 2021 and the final regulations under the RPAA were released in November 2023. The RPAA creates a legislative framework for federal regulation of PSPs. It creates a registration and oversight body within the Bank of Canada which will set and enforce standards for PSPs. At present, these PSPs are largely un- or under-regulated and pose various risks, including the risk of loss of consumer funds (financial risks), the risk of operational and security failures, and market conduct risk.

While the RPAA addresses certain risks related to PSPs, the federal framework is silent on market conduct. With more than 2,500 PSPs currently operating in Canada, and the expectations of increased use and trust that consumers will place in PSPs once they are supervised by the Bank of Canada, the absence of market conduct regulation is a significant gap in consumer protection. Failure to address these risks, among others, can increase risk for consumers and businesses and decrease consumer trust in the financial system.

Financial services and products have the potential to disproportionately impact the well-being of consumers and must be addressed specifically rather than through overarching consumer rights across industries. The CBA and its members are seeking a federal financial consumer protection regime for PSPs commensurate with consumer protection regulations for banks. The preferred approach would be to have a federal framework, developed in consultation with the provinces, that would be adopted in each province to achieve a consistent approach across the country.

We also note there is no legislative review provision within the RPAA. We recommend that a five-year sunset clause be introduced into the RPAA and be reviewed concurrently with the financial sector legislative review going forward. Given the dynamic nature of payments, this will help ensure its relevance and applicability.

Address regulatory compliance burden on banks

Since the GFC, the amount of prudential and market conduct regulation on banks has increased dramatically in order to safeguard the financial system and the broader economy. This is despite Canada’s strong principles-based regulatory oversight contributing to the stability of the Canadian financial sector as well as the critical role the financial sector plays in contributing to key public policy objectives such as affordability and productivity. An efficient and effective financial sector can underpin any government goals to make improvements in these areas.

The number of Guidelines and Advisories OSFI has issued has increased from 26 (since just before the GFC) to 121 in 2022, resulting in 2,749 pages of Guidelines and Advisories that Canadian banks must abide by. This is in addition to legislative and regulatory requirements under the Bank Act as well as market conduct regulations by FCAC. Indeed, in a recent Thomson Reuters Institute survey, legal spending on regulatory matters ranks as the second most likely type of work to increase by Canadian corporate law departments and far ahead of legal spending on the far more productive work area of intellectual property.35

While the federal financial regulatory framework generally takes financial stability and consumer protection into account, not enough consideration is given to implementation costs and their downstream impact on consumers. Financial regulatory changes that do not take into account their operational impacts have imposed considerable compliance costs, which will ultimately be borne by individuals and businesses. While regulations that address financial stability and market conduct regulations may make sense in isolation, when the impact to implementation cost is considered, it may alter the cost-benefit analysis of such a regulation.

When regulators issue new requirements, it would be very beneficial to banks and, ultimately, consumers if the implementation cost was considered throughout the regulatory assessment process. Specifically, this could involve:

- A clear set of measurements used to assess whether the objectives and outcomes have been achieved;

- A framework of minimum requirements to assess whether a regulation is a (net) positive or negative;

- Consultation with parties to determine whether other options may be available, costs, unintended effects and to help understand the benefits of regulation;

- Transparency so all can see the entire process as well as the results; and,

- A republishing of the original objectives and outcomes, the measurement criteria, and research post-evaluation that is made public.

More broadly, steps should be taken to review and rationalize the regulatory burden imposed on the banking sector. An assessment should be undertaken on the competitiveness, effectiveness and stability of the financial services sector, and the contribution of public policy and regulatory requirements to these outcomes. It has been many years since a comprehensive review has been undertaken on the scope of the regulatory regime and whether it contributes to productive outcomes for Canadians. In particular, a review could be undertaken on whether changes to the framework over the years (e.g. increase in capital and other requirements, bank-specific taxes, cost-recovery programs, expanded and contradictory agency mandates/requirements, jurisdictional complexities) are creating unnecessary cost/confusion for consumers, eroding productivity, increasing affordability/inflation concerns, and undermining the stability of the sector as a whole.

Respect the principle of proportionality of regulation for small- and medium-sized banks

It is widely understood that the cost of regulation is scale‑dependent, and therefore an efficient regulatory system needs to have an element of proportionality embedded into it to ensure that it fosters competition.

When done effectively, a proportional framework would allow banks to grow into the level of prudential regulation that suits their overall level of significance or risk to the economy and their level of complexity.

In 2022, OSFI introduced a proportional regulatory framework to give effect to this principle in the prudential regulatory space. While this was welcomed by the industry, small and medium sized banks (SMSBs) are concerned that more recently the Government’s overall commitment to the principle of proportionality has been wavering. While it is generally recognized that regulation needs to evolve as circumstances change, the principle of proportionality needs to remain embedded in the regulatory system.

Such a framework would address capital, liquidity, leverage ratio requirements, as well as supervisory oversight. It should also strive to ensure that SMSBs can compete effectively while maintain acceptable risk parameters that are set by the regulator. For instance, consideration should further be given to regularly reviewing and either addressing the differential between the standardized risk weight and the internal risk‑based (IRB) risk weights or facilitate the use and approval of IRB risk weights. Where the differential between IRB risk weights and standardized weights are excessive, the standardized weigh, which is arbitrary, should be reduced to a level closer to the IRB weight, which is calculated based on actual Canadian data. Excessive differences between standardized and AIRB risk weights have the effect of concentrating the business of standardized banks into a limited set of asset classes, which is problematic from a competitive perspective and also from a financial stability perspective.

Furthermore, this commitment to a proportional regulatory framework is particularly relevant in the current environment as OSFI undertakes its Supervisory Framework Renewal, which will transform the manner in which the regulator reviews and engages with regulated financial institutions. We recommend that OSFI conducts a periodic self‑assessment of its proportional framework, with input from industry, to track progress on ensuring that its regulatory framework is striking the right balance between maintaining safety while enabling effective competition.

Streamline credit union expansion

The CBA has long supported the federal credit union regime option. The regime was created to support growth, consumer choice and seamless expansion of the Canadian credit union system across provincial boundaries and to do so within an appropriate prudential framework that protects the safety and soundness of Canada’s financial system. Credit unions that choose to be federally‑regulated benefit from a robust prudential framework based on the bank model and have the freedom to expand across provincial borders, while recognizing the unique cooperative elements of credit unions. Since the implementation of the federal option in 2012, there have been three credit unions36 that have opted for the federal credit union option, enabling them to provide service to customers across provincial boundaries.

Consideration should be given by the federal government, notably the Department of Finance and OSFI, to facilitate a scenario in which a federal credit union would like to merge with or acquire a provincially regulated credit union. While these transactions generally are permissible under the current framework, the legislation and the regulatory process should be reevaluated to facilitate a process that can be completed by credit unions in a timely manner and where the expectations for both parties are clear, transparent and proportionate to the risks of the transaction. This facilitation would include updated expectations as to what is required by both entities, including information and disclosure requirements as well as OSFI’s expectations for its review of the transaction. This would also include updates to the Bank Act to ensure that (i) the requirements (including approvals) are proportionate to the transaction, (ii) transitional provisions are available for credit unions regardless of the legal structure chosen for the transaction (e.g. amalgamation or asset purchase), and (iii) the process for a federal credit union to acquire the assets of a provincial credit union and for the provincial credit union’s members to become members of the federal credit union is clear and does not create tax exposure to credit unions or members that is inconsistent with comparable transactions between provincial credit unions. Such updated expectations would be beneficial to a competitive and stable financial system.

Make policy and regulatory frameworks digital‑first

While the financial sector was already undergoing rapid and accelerating digitalization (e.g., increased use of online or mobile devices to conduct financial service activities), the pandemic accelerated this trend. Experiences during the pandemic have limited Canadians’ tolerance for inefficient paper‑based and manual processes, and many organizations are looking at ways to move cumbersome processes into the digital realm. As the pandemic has shown us, consumers are now significantly more capable of managing their banking and financial affairs in an electronic manner. This evolution ought to be reflected in the fundamental assumptions for communications between banks and consumers.

Electronic communication

The onerous, unnecessary requirements imposed by the Electronic Documents Regulations (EDRs) under the Bank Act (which date from the early days of electronic communication) fail to recognize the ways in which banks can communicate with their customers in a significantly more timely and cost‑effective way, while still effectively providing information to customers with accessibility in mind. They also fail to recognize how consumers have become significantly more capable of managing their banking affairs electronically. Specifically, the EDRs should be modernized to enable banks to communicate electronically with their customers unless they have been specifically advised by their customers that the customer prefers another form of communication.

Making electronic communications as the default approach would ensure modern business practices and technologies are being used to provide digital documents that are more customer friendly and easier to:

- Search (e.g., via searching one’s email);

- Store (e.g., in one central digital location that does not require physical space); and/or

- Access (e.g., if a customer is disputing an error in a branch or with a phone agent, they don't need to go find the paper document in a box somewhere).

The proposed change could also result in documents becoming more accessible (e.g., can be read aloud by accessibility tools) and enhance the use of "alerts" to notify customers that credit card or other bills are due or have been posted online. The elimination of paper will reduce the significant costs to banks of printing and mailing, tasks involving millions of documents which can impact the cost of banking products and services and can have a detrimental impact on the environment. Finally, we do not believe there is any policy reason to resist the proposed change, as sending a document digitally does not mean the consumer cannot print the document if they feel the need, and customers would still be able to request for documents to be delivered in paper form, if that is their preference.

If the concern is that a customer wants a paper statement to serve as a reminder to pay a bill, allow this issue to be addressed by electronic alerts, the same way that federally‑mandated electronic alerts serve as a reminder when credit cards, lines of credit or deposit account available credit or balances reach specified thresholds. An alert will serve as a reminder to pay a bill in a way that is more effective than a paper bill sitting in a mailbox.

Digital exchange of income and registered plan contribution limit data with taxpayer consent

Currently consumers often rely on paper documents when making important financial decisions such as applying for a mortgage or contributing to their registered plans. Paper documents are administratively cumbersome for consumers as they are not easily accessible and may require locating the documents at home after initiating a home purchase or a contribution to a registered plan or obtaining a copy from the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) through their website or telephone. These paper documents are easily altered or counterfeited, which increases the risk of mortgage fraud, serves to drive up home prices, and undermines confidence in the markets.

A digital exchange of income and registered plan contribution limits between financial institutions with the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) with taxpayer’s consent and implemented with proper authorization and identification criteria and safeguards would address these concerns, ultimately assisting consumers with their financial security while improving customer service. For the CRA, the digital exchange of income and contribution limit data would mean better resource utilization through a reduction in call volumes and wait times. For the federal government, a digital data exchange would curtail instances of mortgage fraud and improve housing affordability. In fact, in its 2022‑23 Annual Risk Outlook, OSFI identified income verification in mortgage underwriting as a key supervisory concern. Similar income verification arrangements are already in place in other jurisdictions such as the U.S. and the U.K. Financial institutions would be able to offer a smoother and more efficient experience to mortgage applicants and their wealth management clients as well as manage mortgage fraud, and better allocate resources.

Repeal section 49 of the Competition Act

Section 49 of the Competition Act makes it illegal and criminal for FRFIs to enter into agreements relating to interest rates, fees or classes of persons served, unless one of several narrow defences applies.

This section was imported into the Competition Act from the Bank Act in 1986, at a point when Canada’s general conspiracy law made competitor agreements illegal only if they prevented or lessened competition unduly. This "unduly" standard became a barrier to cartel prosecution under the Competition Act until the legislation was amended in 2009. The 2009 amendments to the Competition Act removed the "unduly" test for competitor agreements in all industry sectors. With these amendments, there is no longer any need for a special conspiracy offence for FRFIs; however, section 49 remains part of the Competition Act.

A 2016 Banking & Finance Law Review article37 summarizes the case for repeal, noting that section 49 is:

- Redundant following the 2009 amendments;

- Discriminatory because it applies only to FRFIs and not to provincial institutions;

- Ineffective since there has been no enforcement action invoking the section; and

- Costly because it has a chilling effect on pro-competitive collaborations.

The CBA fully endorses these concerns. Despite the absence of any enforcement activity under section 49, consequences of even a technical breach are significant, including large fines, imprisonment, and the potential for civil litigation. Further, unlike the general conspiracy law in section 45 of the Competition Act, there is no exemption under section 49 for conduct that is ancillary to a broader, legitimate agreement.

CBA members are concerned that section 49 may also conflict with the evolving expectations of other regulators when it comes to managing anti money-laundering risk. The Cullen Commission Report38 recommends information sharing and collaboration among financial institutions relating to money laundering, and foreign regulators are taking strong positions to support information-sharing.39 However, information sharing between banks or with other FRFIs to combat money laundering could raise technical risk under section 49(1)(f) since it might lead to an "arrangement" to withhold services from a customer or group of customers, for which none of the defences in section 49(2) would apply. This would create substantial obstacles to legitimate information sharing even if such sharing supports other policy objectives and is supported by other regulators.

Although the Minister of Finance may, in theory, exempt an agreement from the application of section 49 by certifying to the Commissioner of Competition that the Minister has requested or approved the agreement for purposes of financial policy under section 49(2)(h), there is no framework or precedent for reliance on this exemption power. It is not a substitute for a general ancillary restraints defence, and risks politicizing legitimate business conduct.

For all these reasons, the CBA respectfully submits that section 49 of the Act should be repealed.

Remove financial sector‑specific taxes

In recent years, the federal government has specifically targeted the banking industry with sector‑specific taxes including the Financial Institutions (FI) Tax and the Canada Recovery Dividend (CRD). Singling out and taxing a specific industry, particularly one that fuels the economy, is not only bad economic policy but also a detriment to Canada’s competitiveness and economic growth. The cumulative impact of these taxes will impede the flow of money within the system, resulting in slower growth, less job creation and diminished productivity.

These additional taxes on financial institutions will make it harder, or more expensive, for people and businesses to save and borrow money as well as raise capital. It also makes it more difficult to for banks to compete on a global scale, which in turn could have negative repercussions for the wider Canadian economy. Additionally, industry‑specific taxation deters foreign direct investment, hindering our country's capacity to attract essential capital and diminishing our global competitive edge. This will lead to a reduction in the amount of capital available to Canadian businesses and ultimately restricts investment in innovation and economic growth. In addition, they undermine the investments decisions of millions of Canadians who rely on bank equity - either directly or indirectly – to save for their education, down payment, capital projects or retirement.

Financial sector‑specific taxes such as the FI Tax and the CRD should be removed to enable the banking sector to increase investment in Canada’s economy to better serve customers. At a minimum, the FI Tax should be phased out at the same time as the scheduled phase out of the CRD in 2027.

Merger Review Process

Canada has a robust merger review process in place for bank mergers that combines prudential and public interest considerations with an analysis of the impacts of a merger on competition. The CBA and its members do not believe there is a need for significant changes to the current process. In particular, the CBA does not support abandoning the current fact- and evidence‑based analysis of the economic, consumer and public interest impacts of a merger.

Under our current legislative framework, a bank merger may proceed only if the Minister of Finance provides approval under the Bank Act. In making the decision, the Minister of Finance can take into consideration all matters considered relevant, including the best interest of the financial system in Canada, as well as various legislative factors (see Bank Act, section 396). As part of the "best interest" analysis, the Minister also asks the Commissioner of Competition to review bank mergers and issue the Commissioner’s findings on the question of whether the bank merger prevents or lessens competition substantially within the meaning of sections 92 and 93 of the Competition Act.

The key strength of the current framework is that it is principle‑based and flexible in its approach. Proposed mergers could take many forms that may be advantageous for the sector as a whole. As suggested previously, particular level of concentration is not inconsistent with the existence of a competitive framework, and indeed, there may be specific and demonstrable advantages associated with particular merger or acquisition proposals. For example, recent transactions in other jurisdictions have illustrated the benefits of mergers/acquisitions to mitigate systemic risks arising from crisis events. As also suggested previously, the Canadian experience confirms that its levels of concentration does not preclude new players from entering the sector. It is critical to ensure that each proposed transaction is assessed on its own merits and that no proposals are precluded in advance due to the imposition of arbitrary limits or thresholds. The current merger review process is well designed to provide this flexible approach.

Competition law framework

On competition issues specifically, the Competition Bureau’s current framework allows for a detailed, evidence‑based analysis of the impacts of a proposed merger on competition. This analysis relies on the approach to determining whether a merger substantially prevents or lessens competition under the Competition Bureau’s Merger Enforcement Guidelines (MEGs), in line with international competition/antitrust law best practices.

In the view of CBA members, no change is required to the Competition Act merger review process, which is sector‑neutral and principles‑based and has withstood the test of time since it became the law of Canada in 1986.

Bank Act

Under the Bank Act framework, the Minister of Finance may consider such factors as the rights and interests of consumers and business customers; the impact of the transaction on the level of competition in the sector; its consequences for the stability and integrity of the financial sector and public confidence in it. The Minister of Finance has the authority to impose any terms and conditions and to require any undertaking considered appropriate. The range of commitments that the Minister can impose to protect consumers and workers illustrates that the Minister already has considerable remedial jurisdiction and flexibility.

Conclusion

Canadians enjoy a thriving and vibrant financial sector with competition coming from other banks, established financial sector companies, emerging fintech firms with new business models, as well as large multinational technology companies with strong brand presence. As a result, competitive intensity within the financial sector has never been higher due to investments in technology with companies entering, expanding and/or exiting the sector at a rapid pace.

The CBA makes a number of recommendations to allow the financial sector to: better adapt to changing consumer expectations, preferences and behaviours; more effectively incorporate technology; improve consumer protection; apply consistent and proportionate regulatory oversight of companies in the financial sector; increase competition within and the competitiveness of the sector; and with respect to the merger review process. With these changes, an already vibrant competitive financial sector will be made even more competitive.

1 World Bank, The Global Findex Database 2021. Bank account is also known as a chequing or transactional account.

2 Christopher Henry, Doina Rusu, Matthew Shimoda, 2022 Methods-of-Payment Survey Report: Cash Use Over 13 Years, Bank of Canada Staff Discussion Paper 2024-1, January 2024. 57 per cent was derived from the 37 per cent of Canadians that don’t pay an account fee plus the 31 per cent of Canadians with a monthly bank account fee and had it waived or refunded in the last month when surveyed.

3 There are more than 40 banks, over 190 credit unions and close to 210 caisses populaires as well as ATB Financial that offer bank accounts. Bank accounts are also known as chequing or transactional accounts.

4 Several of the recommendations have also been detailed in the CBA’s submission to the Department of Finance, submitted on December 4th, 2023, as part of the response to the Consultation on Upholding the Integrity of Canada’s Financial Sector (Financial Institutions Statutes Review) as well as the CBA’s Pre-Budget submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance, submitted on August 4th, 2023.

5 Tracxn, as of June 16, 2023.

6 Banks that are authorized to operate on a branch basis are not permitted to accept deposits of less than $150,000, an amount used to distinguish between retail and wholesale deposits.

7 In December 2002, there were 70 banks - 16 domestic banks (Schedule I), 33 foreign bank subsidiaries (Schedule II) and 21 foreign bank branches (Schedule III). In December 2022, there were 80 banks - 34 domestic banks (Schedule I), 15 foreign bank subsidiaries (Schedule II) and 31 foreign bank branches (Schedule III).

8 The two financial sector companies seeking approval for a domestic banking license are Koho Financial and Questrade Finance Group.

9 The World Bank Group; DataBank – Global Financial Development, 2023.

10 OECD, Executive Summary of the hearing on Market Concentration - Annex to the Summary Record of the 129th Meeting of the Competition Committee held on 6-8 June 2018.

11 CapGemini World Retail Banking Report 2011-2016. Canadian retail banking customers ranked their banks 2nd in 2011 and 1st in between 2012-2016 for customer satisfaction. The Customer Experience Index asked questions about customer preferences, expectations and behaviors with respect to specific types of retail banking transactions. The survey questioned customers on their general satisfaction with their bank, the importance of specific channels for executing different types of transactions, and their satisfaction with those transactions, among other factors. The survey also questioned customers on their trust and confidence in their bank, their perception around the understanding that their bank has of their needs, the degree of product-channel fit and consistent multi-channel experience provided by their bank, why they choose to stay with/change their bank, their perceived importance of different services provided by their bank, and other issues.

12 CapGemini World Retail Banking Report 2012.

13 Acting Comptroller of the Currency Michael J. Hsu, "What Should the U.S. Banking System Look Like? Diverse, Dynamic, and Balanced" University of Michigan School of Business, January 29, 2024.

14 World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report

15 BrandFinance 2023 Annual Report

16 Global Finance, World’s Safest Banks 2023 – Global Top 100.

17 Canadian Bankers Association (CBA), How Canadians Bank, Abacus Data, 2021.

18 CBA data.

19 CBA data.

20 Evident AI Index. The November 2023 Index covers 50 of the largest banks in North America, Europe, and Asia. Each bank is assessed on 100+ individual indicators drawn from millions of publicly available data points specific to four pillars: Talent, Innovation, Leadership, and Transparency.

21 Canadian Bankers Association (CBA), How Canadians Bank, Abacus Data, 2021.

22 CCUA National System Results 2023, December 2023.

23 World Bank, The Global Findex Database 2021.

24 Christopher Henry, Doina Rusu, Matthew Shimoda, 2022 Methods-of-Payment Survey Report: Cash Use Over 13 Years, Bank of Canada Staff Discussion Paper 2024-1, January 2024.

25 Ibid.

26 CMHC National Housing Act Approved Lenders.

27 World Bank, The Global Findex Database 2021.

28 Mortgage Professionals of Canada (MPC), Semi-Annual State of the Housing Market, March 2022.

29 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), Footprint of FinTechs in the Canadian Mortgage Market. October 2020. Research Insight: Footprint of FinTechs in the Canadian Mortgage Market (cmhc-schl.gc.ca)

30 Ibid.

31 According to ISED’s 2022 Credit Conditions Survey, 18% of SMEs required debt financing in 2022.

32 According to Statistics Canada’s Survey of Suppliers of Business Financing, these 120 companies represent over 90 percent of all lending to businesses in Canada.

33 According to ISED’s Survey of Financing and Growth of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises 2020, March 2022, less than 1% of SMEs obtained financing from online alternative lenders or crowdsourcing or peer-to-peer lenders.

34 Ibid.

35 Thomson Reuters Institute, 2023 Canadian Legal Market Update. Net spend optimism (NSO) is calculated as the difference between the percentage of law departments anticipating a decrease in legal spend over the next 12 months subtracted from the percentage of law departments anticipating an increase in legal spend during that time. For example, NSO for regulatory was 11 points, as 25% of respondents said they expect spending to increase while only 14% said they expect spending to decrease. Conversely, NSO for intellectual property was 2 points, as 15% of respondents said they expect spending to increase while only 12% said they expect spending to decrease.

36 Caisse populaire acadienne ltée (UNI Financial Cooperation), Coast Capital Savings Federal Credit Union and Innovation Federal Credit Union

37 Marina Chernenko, "The Price of a Dormant Provision: Revisiting Section 49 of the Competition Act", 31 B.F.L.R. 601 (2016).

38 Cullen Commission, Consolidated Recommendations of the Commission of Inquiry into Money Laundering in British Columbia. See recommendation 48.

39 For example, the UK government’s Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill, 2022 proposes the following use case: A bank that decides to terminate a relationship with a customer due to economic crime concerns may share relevant personal information with other banks so that any future bank that the individual might apply to, is aware of their decision. The government emphasizes that this sharing would provide more data to enable banks to make risk-based decisions, but would not provide any new powers to make decisions to restrict or exclude customers (i.e., banks must ensure decisions are free from bias and any unlawful discrimination).